I’m a fan of 90s music, in that it was what I listened to as a teenager and know something about, and not because I’m the kind of middle-aged man who starts ranting at young people about it somehow being objectively better than whatever they like to listen to.

Apparently, though, lots of young people like Oasis, because — according to news reports over the summer — they were among the many trying to get tickets for next year’s reunion gigs, annoying the same group of middle-aged men who are always going on at them to listen to ‘real music’.

They can’t win, can they, the young people? Should they stick to their young people music, which objectively isn’t as good as the old stuff, or should they actually get into the old stuff because it’s better, while running the risk of denying some blokes who’ve already been to see Oasis seven times the opportunity to go again, with all involved years past their peak, at a cost of several hundred quid?

Anyway, there’s a lot more to 90s music than Britpop, you know - it wasn’t all just a load of blokes with guitars! (No, I couldn’t get tickets for Oasis, either).

—

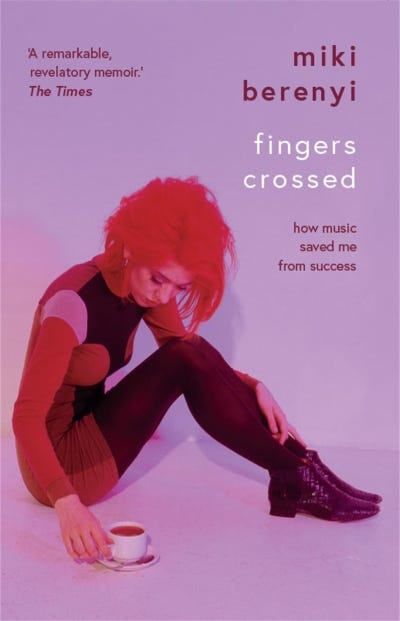

Fingers Crossed: How Music Saved Me From Success

Miki Berenyi (Nine Eight Books, 2022)

Lush were one of those bands whose early records predated Britpop and baulked at being described as Britpop, while also releasing an album at its height — 1996’s Lovelife — that featured radio-friendly, guitar-led pop singles that would very much pass for the kind of thing that people might describe as Britpop.1

Each time mid-90s ‘Cool Britannia’ stuff is reheated in the media, the counterpoint — that it’s been mythologised after the fact, often by people who weren’t there, and was in reality completely terrible — is rarely far behind. In fact, the argument goes, Britpop was musically and socially regressive, everyone involved was on loads of drugs and behaving like twats, and — by the way — Country House by Blur and Roll with It by Oasis were two of the worst singles released by each band.

That’s certainly the position of former Lush lead singer Miki Berenyi, who sums up her thoughts at the end of an entertainingly frank chapter of Fingers Crossed thus: ‘Sorry for being a party pooper, I know a ton of you had a blast, but I fucking hate Britpop and I’m glad the whole sorry shit-fest ended up imploding.’

The teenage Berenyi was a music fan, a dedicated attender of gigs in the less-fashionable 80s, with her involvement in Lush an extension of that love for music, as well as an escape from a difficult and transient home life.

When the 90s came around, and her attendance at the same gigs as high-profile Britpoppers was suddenly interpreted by the music press as insincere and part of a desperation to be seen in the same places as famous people, it’s no surprise that she would rail against it all: ‘If anyone’s the fucking interloper, it’s them,’ she snarls, after being sneered at by Blur’s Graham Coxon.

The toxicity of music journalism at the time is covered in some detail, and there’s no glossing over the fact that relentless mean-spirited bitchiness and gossip was its stock-in-trade. It’s a tone that may seem a complete anathema to anyone who didn’t experience it at the time: in a pre-social media world, cruelty was largely left to the professionals and then circulated in hard copy before it could ferment among the general public.

Before Lush, Berenyi experienced a most unusual and frequently troubled childhood: the daughter of a Japanese actress, Yasuko, and a Hungarian journalist, Ivan, she chafed against the capricious nature of her stepfather, stuntman-turned-director Ray Austin, who apparently faked heart attacks whenever he was losing an argument.

As a result, she instead found herself living with a hopeless and often absent Ivan, and his mother Nora — a Nazi sympathiser during the war, and unrepentant ever since — whose caregiving sometimes strayed into abuse.

Berenyi’s anger has a limit — for her own sake, she argues: ‘You can get mired in blame and excuses trying to figure out which bit of your past makes you behave in certain unacceptable and self-defeating ways… At some point, I had to accept the damage and move on. Otherwise, you’re just letting the fuckers win.’

Her subsequent transfer to a private school, at her mother’s behest, led to Berenyi meeting future Lush bandmate Emma Anderson, but also meant that the band were characterised as privileged and inauthentic by some in the press. In Berenyi’s case, at least, that seems particularly unfair.

A slightly tempestuous relationship between Berenyi and Anderson is a running theme throughout the book: it wasn’t what first broke the band up in 1996, although it appears to have been a factor in the swift end to the Lush reunion twenty years later, a period given very little further consideration, or sketched out in any detail, here.

If the fairy-tale happy ending — of older people getting together again, deciding that all of their previous tensions and fights of many years ago were rather silly and immature, and putting it all behind them2 — proves to be elusive in this case, Berenyi ends her story in good shape.

While she expresses a level of contentment with life after leaving the industry behind in the 90s to do a ‘normal job’, it seems fitting that by the time Fingers Crossed ends, music has – through the band Piroshka (featuring partner KJ ‘Moose’ McKillop) and the Miki Berenyi Trio – become part of her life once again.

—

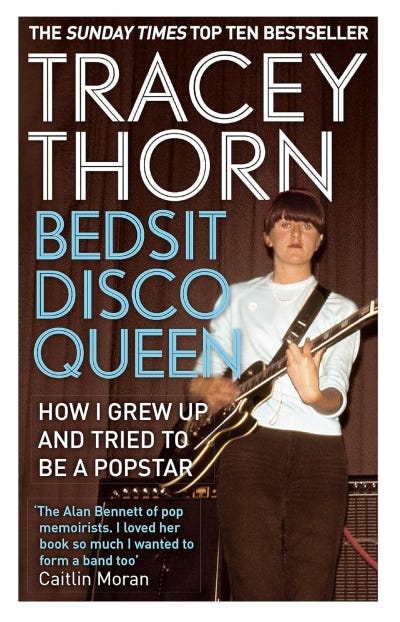

Bedsit Disco Queen: How I Grew Up and Tried to Be a Popstar

Tracey Thorn (Virago, 2013)

If part of getting older involves retrospectively forgiving pop songs from your childhood that used to get on your nerves because they were aggressively and relentlessly overplayed, then Missing by Everything But The Girl would certainly be on my list.3

Back in 1995, it seemed to be constantly hogging the airwaves, regardless of your chosen station,4 and I quickly grew tired of hearing it repeatedly, figuring somewhat dismissively that it was a likely one-hit wonder that would eventually go away, along with the band itself.

This was wrong on many levels, not only because Everything But The Girl had several other hits,5 but also because EBTG — a duo comprising Thorn and husband Ben Watt — were really an 80s indie band, not a 90s house act, who achieved unexpected and belated success with a Todd Terry remix of a song from their eighth album.

Those coming to Thorn’s memoir Bedsit Disco Queen with an expectation of 90s pop and rock gossip, like the salivating dogs that all people who buy two books for £7 from one of the few remaining branches of HMV definitely are,6 will instead find — of course — a more rounded account of her life and career in music.

There are a number of parallels with Miki Berenyi’s tale as told in Fingers Crossed: despite very different childhoods, music also represented an escape for Thorn, although in her case it was from the boring comfort of a suburban upbringing, and early gig-going soon developed, as it did for Berenyi, into the formation of a post-punk band,7 with the author reluctantly pushed onto vocal duties after the departure of the original singer.

Much later, after EBTG had experienced some chart success with a cover of Rod Stewart’s I Don’t Want To Talk About It in 1988, the duo were also made to feel uncomfortable while supposedly in their element at a live music venue: a couple of ‘studenty Beavis and Butthead types’ are observed snickering at the duo while attending a concert at the University of London Union:

‘“Look, I-don’t-wanna-talk-about-it,” chuckled one, and his mate quipped back, “I-don’t-wanna-hear-about-it”... Had we suddenly become people who were not supposed to be at a [late 80s US indie rock band] Galaxie 500 gig? How on earth had THIS happened?’

In general, the tone of Bedsit Disco Queen is rather more sanguine, however, with Thorn not hiding her own early indie snootiness but viewing it with some amusement, and distance, as the stubbornness of a younger person.

Britpop, meanwhile, is given a more sympathetic hearing: although EBTG’s success coincides, on the back of Missing, Thorn views it all as a complete accident, many years after the band thought they would ever achieve it, and is therefore able to enjoy the ride, finding herself in the same space as mega-famous people without ever feeling like a part of it.8

Some perspective is perhaps not surprising given the health struggles of long-term musical and life partner Watt. As rock and pop relationships go, it appears to have been incredibly stable: after meeting at the University of Hull in 1981, they soon became inseparable, and seemingly managed to successfully negotiate the ups and downs of their shared lives and careers as a partnership.

However, a decade later, Watt was hospitalised after suddenly becoming ill with a rare autoimmune disease, a complicated diagnosis requiring life-saving treatment that brought all musical and touring activities to a swift halt.

After the surprise of a late-career renaissance, in the second half of the 90s, Thorn was happy to simply stop and focus on different priorities. As Bedsit Disco Queen ends, working with Watt again as EBTG appears to be a distant prospect. However, while Thorn remains retired from performing live, they did subsequently release another album, Fuse, to a warm critical reception in 2023.

It’s an appropriate postscript to this tale, largely free of angsty gossip or drama, while still offering plenty of insight for music fans regardless of their particular fondness for the band, or indeed their irritation at hearing Missing in the 90s. (Which, incidentally, I was wrong about all along: it’s a stone-cold banger).

My personal favourite is Single Girl, the wedding-based video for which features two actors from Four Weddings and a Funeral — Simon Kunz (‘Any kids or anything, John? Do we hear the patter of tiny… feet? No. Well, there’s plenty of time for that, isn’t there?’) and Polly Kemp (‘We’ve BOTH lost a lot of weight since then!’)

This doesn’t seem like an especially likely outcome for the Oasis reunion, either, although to be fair, the Gallagher brothers did somehow manage to remain in the band together for over 15 years in the first place.

In fact, I’d say I’m fairly close to a clean slate by now when it comes to most songs from the 90s, although I might need another five years or so before listening to Lovefool by The Cardigans again.

I mean, unless it was Radio 3 or something. You know what I mean.

Most pop acts that are remembered as a one-hit wonder usually had at least one similar-sounding and less successful follow-up that made the charts, although I was recently recounting this theory to a friend, prepared with details of second hit singles by Whigfield (Another Day, sounded exactly like Saturday Night) and Rednex (Old Pop in an Oak, sounded exactly like Cotton Eye Joe) and she stopped me in my tracks by saying ‘Except Breakfast at Tiffany’s by Deep Blue Something’.

(I mean, we can all go on Wikipedia and find out that a follow-up song called Josey got to number 27, but who remembers it, really?)

Coincidentally, Breakfast at Tiffany’s was knocked off the number 1 spot by Setting Sun, a collaboration between Noel Gallagher and The Chemical Brothers, which led me to this interview in The Quietus, during which a characteristically modest Noel posits that he did the charts a favour: ‘We were like Sir Galahad… off with your head, you piece of shit!’

I say this as one of those salivating dogs, although the books section at HMV is a a curious thing in the year 2024: roughly 1/3 books by comedians, 1/3 books by or about musicians, and 1/3 ‘edgy’ fiction – a selection of pop culture shortcuts from a bygone, pre-internet age, when tedious blokes would try and impress girls by saying things like, ‘You know that movie, Fight Club? It’s actually based on a book.’

Genuine showbiz anecdote: Beach Party, by Thorn’s band Marine Girls, appeared on a list of Kurt Cobain’s 50 favourite records when his journals were published in 2002. Courtney Love had also said as much to Thorn when the two met while filming The Word in 1994.

Thorn also worked with Massive Attack in the 90s, although on the evidence of this book, their relationship appears to have mainly been characterised by a mutual low-level bemusement.